The natural history of disease in adults with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is poorly understood. Pulmonary LCH is the exception to this finding. Delays of many months or years commonly occur before adults are diagnosed, and they have long-term issues with chronic pain and fatigue. There are other differences from childhood LCH, including frequency of various bone sites of disease. It also appears that multisystem high-risk LCH in adults may be less aggressive than high-risk disease in children. A consensus group reported on the evaluation and treatment of adult patients with LCH.[1] However, treatment discussions continue, particularly regarding optimal first-line therapy.

A multicenter retrospective review of 219 adult patients (aged >18 years) with LCH was conducted to assess long-term outcomes. The median follow-up was 74 months. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 58%, and the overall survival (OS) rate was 88%. About one-third of deaths were LCH-related and occurred within 5 years of diagnosis. Second cancers occurred in 16.4% of cases (both hematologic and solid tumors). Deaths that occurred 5 or more years after diagnosis were predominantly non-LCH related (i.e., second cancers, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease). Compared with the general U.S. population, patients with LCH had a higher standard mortality ratio (SMR) if diagnosed before age 55 years (SMR, 5.94) or had multisystem disease (SMR, 4.12).[2]

Clinical Presentation

Adult patients may have signs and symptoms of LCH for many months before receiving a definitive diagnosis and treatment. LCH in adults is often similar to that in children and appears to involve the same organs, although the incidence in each organ may be different. There is a predominance of lung disease in adults, usually occurring as single-system disease and closely associated with smoking and some unique biological characteristics. Most isolated lung LCH cases in adults are polyclonal and possibly reactive, while fewer lung LCH cases are monoclonal.[6,7]

A German registry with 121 registrants showed that 62% had single-organ involvement and 38% had multisystem involvement. Pulmonary LCH occurred in 34% of the total study population. Lungs are the most common site, followed by bone and skin involvement. The median age at diagnosis was 44 years (±12.8 years). All organ systems found in childhood LCH were seen in these adults, including endocrine and central nervous system (CNS), liver, spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract. The major difference is the much higher incidence of isolated pulmonary LCH in adults, particularly in young adults who smoke. Other differences appear to be the more frequent involvement of genital and oral mucosa.[8]

Presenting signs and symptoms from published studies include the following:

- Dyspnea or tachypnea.

- Polydipsia and polyuria.

- Bone pain.

- Soft tissue swelling near bone lesions.

- Skin rash or scalp nodules.

- Lymphadenopathy.

- Weight loss.

- Fever.

- Gingival hypertrophy.

- Ataxia.

- Memory problems.

- Hepatosplenomegaly.

Patients who present with isolated diabetes insipidus should be carefully observed for the onset of other signs or symptoms characteristic of LCH. At least 80% of patients with diabetes insipidus had involvement of other organ systems, including bone (68%), skin (57%), lung (39%), and lymph nodes (18%).[9] However, isolated diabetes insipidus in adults is similar to that in pediatric patients, with progression from posterior to anterior pituitary/hypothalamus and to cerebellar involvement. For more information, see the Endocrine system section.

Skin and oral cavity

Thirty-seven percent of adults with multifocal LCH have skin involvement. Skin-only LCH occurs but it is less common in adults than in children. The prognosis for adults with skin-only LCH is excellent, with a 5-year survival probability of 100%. The cutaneous involvement is clinically similar to that seen in children and may take many forms.[10] Infra-mammary and vulvar involvement are frequent sites of presentation in adult women.

Many patients have a papular rash with brown, red, or crusted areas ranging from the size of a pinhead to a dime. In the scalp, the rash is similar to that of seborrhea. Skin in the inguinal region, genitalia, or around the anus may have open ulcers that do not heal after antibacterial or antifungal therapy. The lesions are usually asymptomatic but may be pruritic or painful. In the mouth, swollen gums or ulcers along the cheeks, soft or hard palate, gingiva, or tongue may be signs of LCH.

Diagnosis of LCH is usually made by skin biopsy performed for persistent skin lesions.[10]

Bone

The relative frequency of bone involvement in adults differs from that in children. The frequency of mandible involvement is 30% in adults and 7% in children, and the frequency of skull involvement is 21% in adults and 40% in children.[8,9,11,12] The frequencies of lesions in the vertebrae (13%), pelvis (13%), extremities (17%), and ribs (6%) in adults are similar to those found in children.[8]

Lung

Pulmonary LCH in adults (40%–50% of patients) is usually single-system disease. However, in some patients, other organs may be involved, including bone, skin, and hypothalamus/pituitary.[13]

Pulmonary LCH is more prevalent in smokers than in nonsmokers, and the male-to-female ratio is nearly 1:1, depending on the incidence of smoking in the population studied.[13,14] However, a study of pulmonary LCH from China reported that 73% of the patients were male.[15] Patients with pulmonary LCH usually present with a dry cough, dyspnea, or chest pain, although nearly 20% of adults with lung involvement have no symptoms.[16,17] Chest pain may indicate a spontaneous pneumothorax (10%–28% of adult pulmonary LCH cases).[15]

Pulmonary LCH can be diagnosed by bronchoscopy in about 50% of adult patients, as defined by immunostaining of at least 5% of CD1a-positive cells in the sample.[18] High-resolution lung computed tomography (CT) shows characteristic changes with cysts and nodules, more prevalent at the mid and upper zones. These findings have been characterized as pathognomonic for lung LCH.[16]

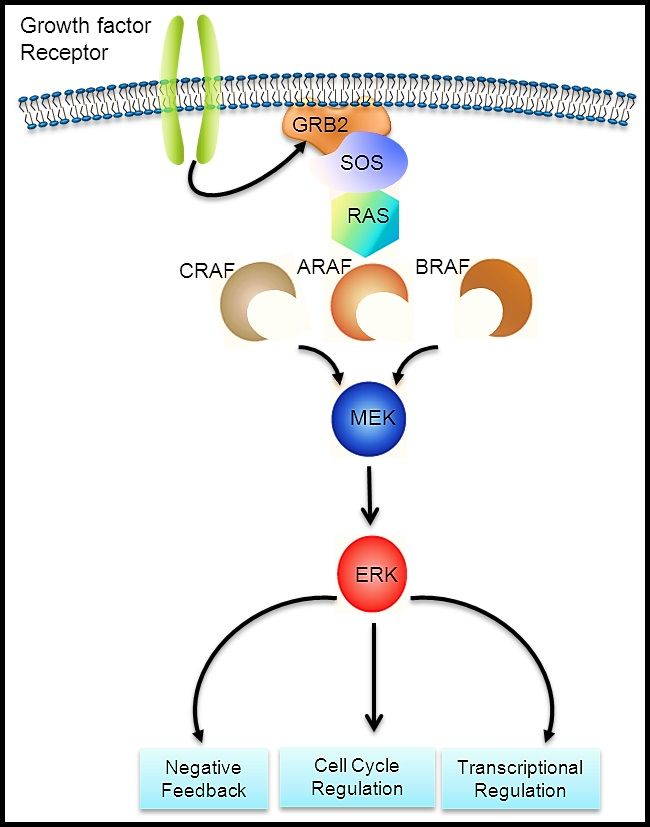

The LCH cells in adult lung lesions were shown to be mature dendritic cells expressing high levels of the accessory molecules CD80 and CD86, unlike Langerhans cells (LCs) found in other lung disorders.[17] MAPK pathway variants have been demonstrated in more than two-thirds of pulmonary LCH lesions in adults, suggesting a clonal process in a significant proportion of patients.[7,19]

In a review of 206 patients with pulmonary LCH from France (median follow-up, 5 years), the 10-year survival rate was 93%.[20] Patients who had chronic respiratory failure or pulmonary hypertension, both less than 5% of the study group, had much worse outcomes. Of these patients, 58% died. Patients with pulmonary LCH had a 17-fold higher incidence of lung carcinomas than an age- and sex-matched French population cohort.

Favorable prognostic factors for adult LCH of the lung include the following:

- Minimal symptoms. Adults with pulmonary LCH who have minimal symptoms have a good prognosis, although some have steady deterioration over many years.[5]

- Smoking cessation or treatment. Fifty-nine percent of patients do well with either spontaneous remission after cessation of smoking, or with some form of therapy.[5] However, one study reported that smoking cessation did not increase the longevity of adults with pulmonary LCH, apparently because the tempo of disease is so variable.[21] The authors of the review of 206 patients from France (see above) [20] noted that the two studies cited here had fewer patients, were retrospective, and did not perform high-resolution CT scans as frequently.[5,21] These older studies likely included patients with more severe disease than the French study.[20]

- Lung transplant. In one multicenter study, patients who received lung transplants for the treatment of pulmonary LCH had a 1-year survival rate of 77% and a 10-year survival rate of 54%, with a 20% chance of LCH recurrence.[22]

Unfavorable prognostic factors for adult LCH of the lung include the following:

- Altered pulmonary function. Lower forced expiratory volume/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio and higher residual volume/total lung capacity (RV/TLC) ratio are adverse prognostic variables.[21] Some patients have normal ventilatory function but abnormal carbon monoxide diffusion capacity.[15][Level of evidence C2] About 10% to 20% of patients have early severe progression to respiratory failure, severe pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale. Adults who have progression with diffuse bullae formation, multiple pneumothoraces, and fibrosis have a poor prognosis.[23,24]; [15][Level of evidence C2]

- Age. Age older than 26 years is an adverse prognostic variable.[21]

- Smoking.

Most patients have a variable course, with stable disease in some patients and relapses and progression of respiratory dysfunction in others, often after many years.[25] A natural history study of 58 patients with pulmonary LCH found that 38% had deterioration of lung function after 2 years.[26] The most significant adverse prognostic variables were positive smoking statuses and low PaO2 levels at the time of inclusion.

The following results may be noted on diagnostic tests:

- Pulmonary function testing. The most frequent pulmonary function abnormality finding in patients with pulmonary LCH is a reduced carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, which is found in 70% to 90% of cases.[21,27]

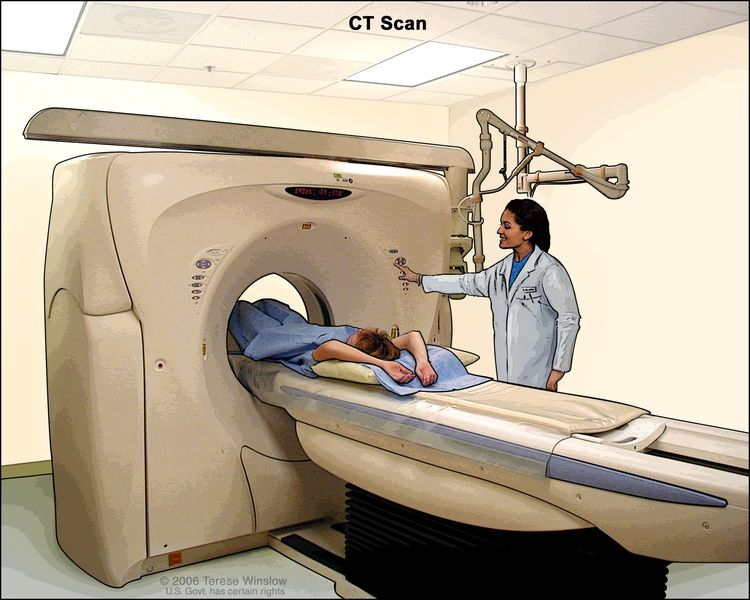

- CT scan. A high-resolution CT scan, which reveals a reticulonodular pattern with cysts and nodules, usually in the upper lobes and sparing the costophrenic angle, is characteristic of LCH.[28] The presence of cystic abnormalities on high-resolution CT scans appears to be a poor predictor of which patients will have progressive disease.[29]

- Biopsy. Despite the typical CT findings, most pulmonologists agree that a lung biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. A study that correlated lung CT findings and lung biopsy results in 27 patients with pulmonary LCH observed that thin-walled and bizarre cysts had active LCs and eosinophils.[30]

Liver

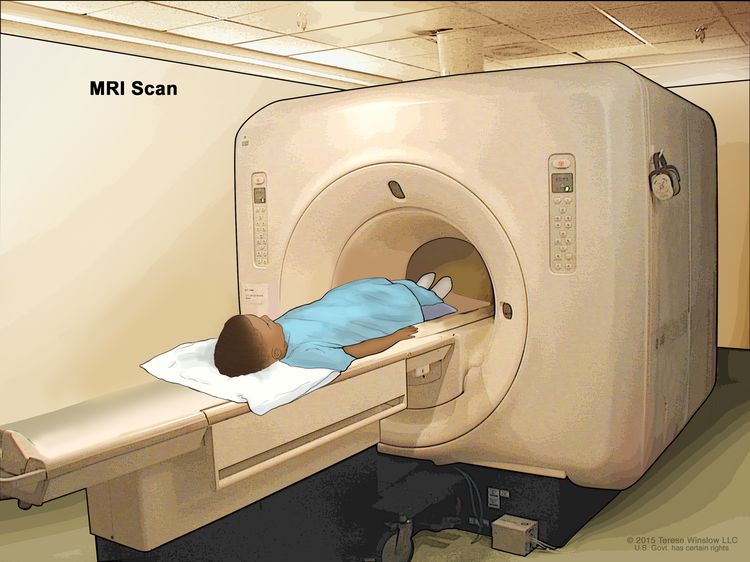

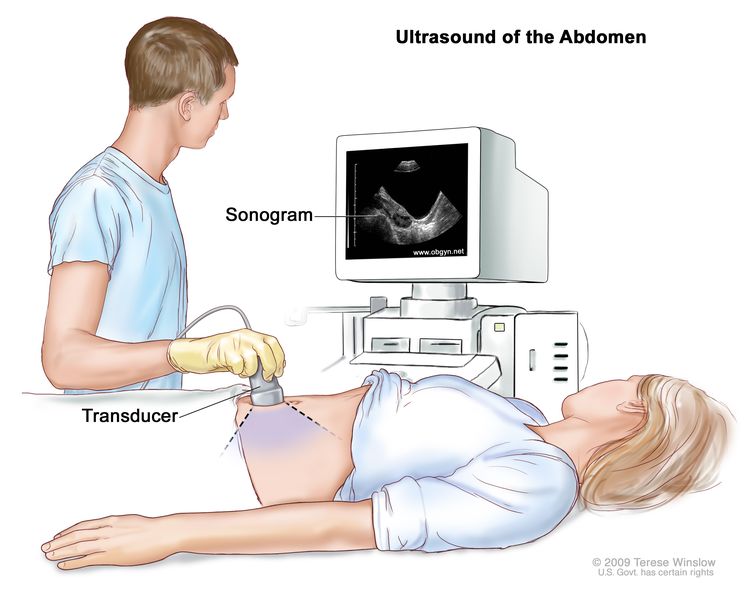

In one study, liver involvement was reported in 27% of adult patients with multiorgan disease.[31] Hepatomegaly (48%) and liver enzyme abnormalities (61%) were usually present. CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasonography imaging often find abnormalities along the biliary tract.

The early histopathological stage of liver LCH includes infiltration of CD1a-positive cells and periductal fibrosis with inflammatory infiltrates with or without steatosis. The late stage is biliary tree sclerosis. Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid may be helpful.[31]

Endocrine system

Diabetes insipidus occurs in 25% of patients and may precede the diagnosis of LCH.[9] Anterior pituitary abnormalities are seen in approximately 20% of these patients.[32] Sometimes imaging studies of the pituitary are normal.[33]

Central nervous system (CNS)

The most frequent abnormalities in the CNS are enlargement of the pituitary, its stalk, and/or the hypothalamus. Brain involvement is typically in the cerebellum, pons, and basal ganglia, with abnormalities seen on the T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. Some patients have only imaging changes, but others have ataxia, dysmetria, dysarthria, and behavioral and psychological difficulties.[34]

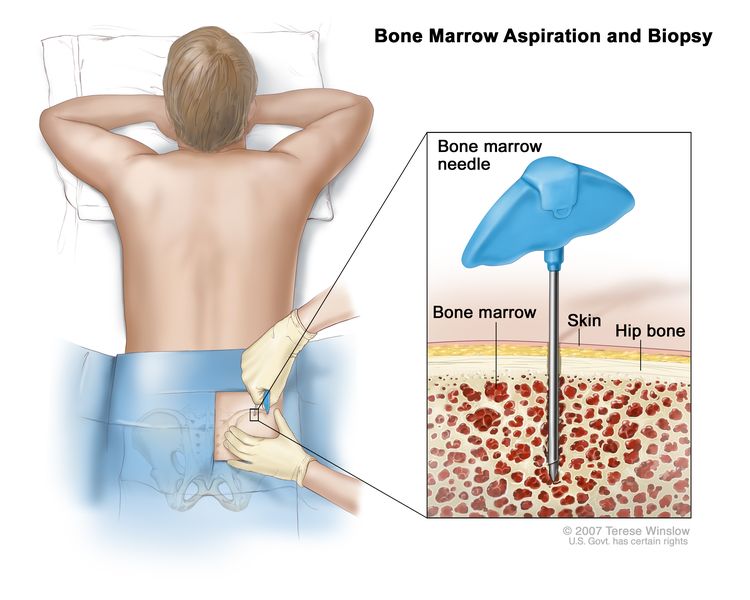

Bone marrow and lymph nodes

Bone marrow involvement with LCH is uncommon and is usually heralded by abnormal blood counts, which could also be a sign of an underlying malignancy.[35] Lymph node infiltration in LCH is uncommon as an isolated finding, but can occur in up to 30% of patients with multisystem LCH.[34]

Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems

Gastrointestinal involvement is rare and usually presents with diarrhea and pain.[36] Abnormalities in the heart or around the great vessels often suggest a hybrid disease of Erdheim-Chester (ECD) and LCH.[37]

Multisystem disease

In a large series of patients from the Mayo Clinic, 31% had multisystem LCH, compared with 69% registered on the Histiocyte Society adult registry. This finding likely reflects referral bias.[10,38] In the adult patients with multisystem disease, the sites of disease included the following:

- Skin (50%).

- Mucocutaneous (40%).

- Pituitary/CNS (diabetes insipidus, 29.6%).

- Liver/spleen (hepatosplenomegaly, 16%).

- Thyroid (hypothyroidism, 6.6%).

- Lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy, 6%).

LCH and associated malignancies

Adult patients with LCH have higher rates of malignancies than do age-matched patients without LCH, by ratios of 2 to 4, depending on patient age.[39] A review of 132 patients with LCH from a single institution found 31 patients with other malignancies before their LCH diagnosis, 11 patients with concurrent malignancies, and 11 patients with other malignancies after their LCH diagnosis. Solid tumors comprised 74% of the malignancies, lymphomas comprised 17% of the cases, and hematologic malignancies comprised 9% of the cases. Seventy-one percent of the patients were smokers.[39] These results are in contrast to an earlier study that was based on a literature review and institutional surveys that reported a higher incidence of lymphomas concurrent with the LCH diagnosis.[40]

The association between LCH and malignancy occurs more frequently than would be expected by chance, based on questionnaires sent to investigators in the Histiocyte Society and a literature review. In one publication, LCH-malignancy cases were collected between 1991 and 2015. A total of 285 LCH-malignancies were seen in 270 patients. In 154 adults with LCH, solid tumors were reported in 61 patients (39.6%), lymphomas in 56 patients (36.4%), and leukemias and myeloproliferative disorders in 37 patients (24.0%). Thyroid malignancy was also seen with some frequency. In adults, LCH and malignancy occurred concurrently in 69 patients (44.8%).[41]

A review of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data for subsequent malignancies in 456 adults with LCH found 16 cases.[42] There were two cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, two cases of myelodysplastic neoplasms, three cases of breast cancer, three cases of lung cancer, and one case each of colorectal cancer, thyroid cancer, vulvar cancer, meningioma, and adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified.

A study of 156 adults with LCH reported on the relationship of LCH with the BRAF V600E variant and secondary primary malignancies.[43] Patients with LCH and the variant had a 17.3% incidence of second primary malignancies, compared with 4.1% for patients without the variant. The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) was 5.72 for second malignancies in patients with LCH, compared with 1.7 in age-matched adults. Unlike children with LCH, there was no correlation with the extent of the disease or progression-free survival in adults with BRAF V600E variants.