Childhood Tracheobronchial Tumors (PDQ®)–Patient Version

What are childhood tracheobronchial tumors?

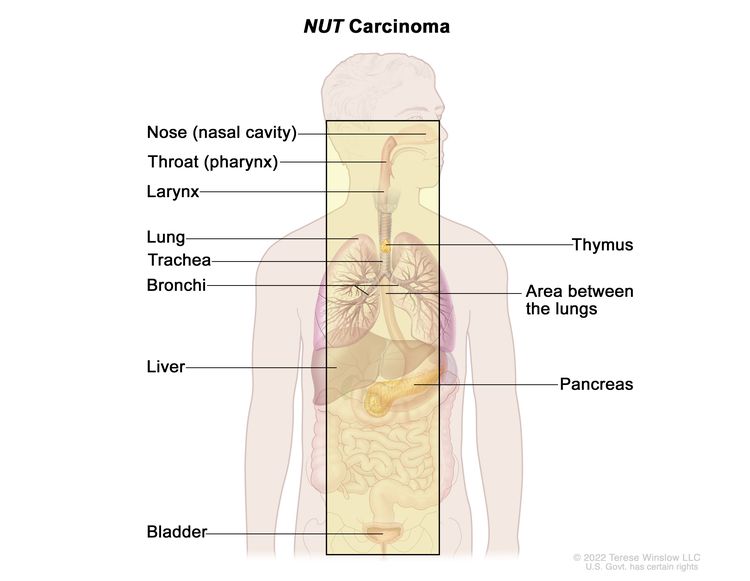

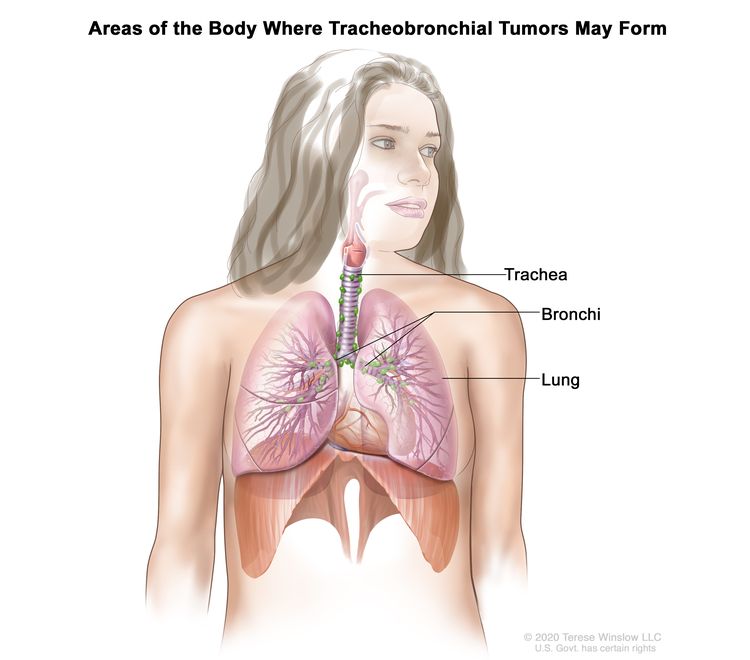

Tracheobronchial tumors are rare, abnormal growths that form in the windpipe (trachea) or the large airways in the lungs called the bronchi. They can be benign (not cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Benign tumors are more common in children. If a child has a benign tumor, they may need treatment to prevent the tumor from growing and putting pressure on nearby tissue in the airway. If the tumor is cancerous, the treatment is aimed at killing the cancer cells and keeping them from spreading to other parts of the body.

Several types of tracheobronchial tumors may affect children:

- Carcinoid tumor is the most common type of tracheobronchial tumor in children. This type of tumor is usually benign, but some may be cancerous and spread to other parts of the body.

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a slow-growing cancer that affects the airway.

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is a slow-growing tumor that usually affects the upper trachea. These tumors rarely spread to other parts of the body.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. Learn more at Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment.

- Granular cell tumor is usually benign, but can be cancerous and spread to nearby tissue.

Causes and risk factors for childhood tracheobronchial tumors

Tracheobronchial tumors in children are caused by certain changes to the way cells in the lining of the trachea or large bronchi function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of these cell changes is unknown. Learn more about how cancer develops at What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. There are no known risk factors for childhood tracheobronchial tumors.

Symptoms of childhood tracheobronchial tumors

Symptoms of tracheobronchial tumors are a lot like symptoms of asthma, which can make it hard to diagnose the tumor. It’s important to check with your child’s doctor if your child has any symptoms, such as:

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than a tracheobronchial tumor. The only way to know is to see your child’s doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood tracheobronchial tumors

If your child has symptoms that suggest a tracheobronchial tumor, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or to another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child’s personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with a tracheobronchial tumor, the results of these tests will help you and your child’s doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose tracheobronchial tumors in children may include:

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of radiation that can go through the body and make pictures. A chest x-ray makes pictures of the organs and bones inside the chest.

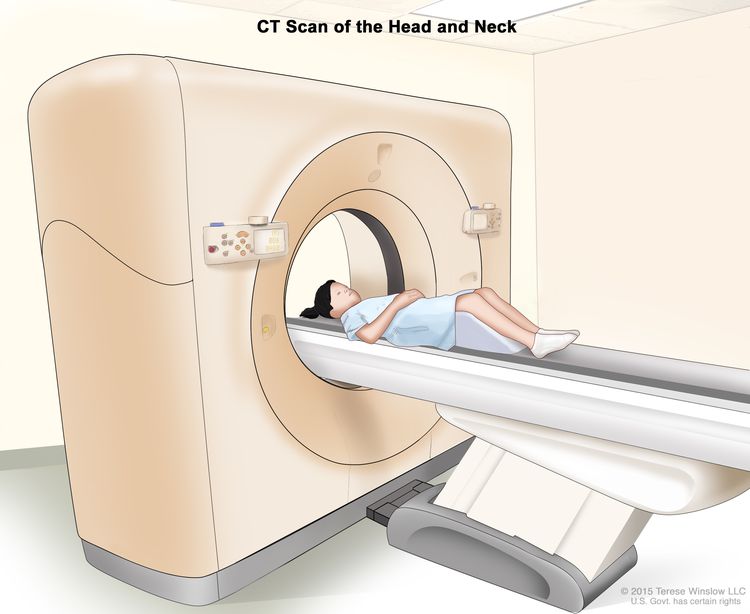

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the neck and chest. The pictures are taken from different angles and are used to create 3-D views of tissues and organs. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. Learn more about Computed Tomography (CT) Scans and Cancer.

Bronchoscopy

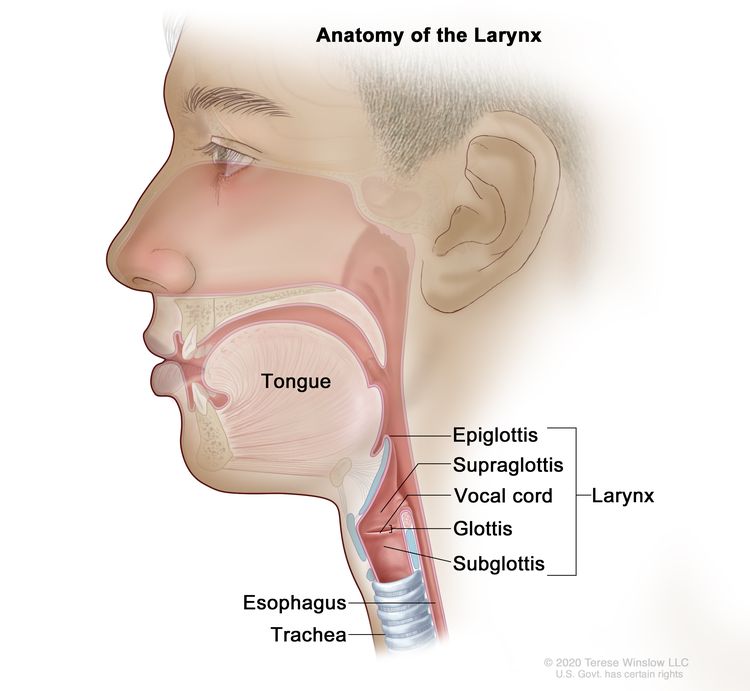

Bronchoscopy is a procedure to look for abnormal areas inside the trachea and large airways in the lung. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

Bronchography

Bronchography is a procedure to look for abnormal areas in the larynx, trachea, and bronchi and to check whether the airways are wider below the level of the tumor. A contrast dye is given through a bronchoscope to coat the airways and make them show up more clearly on x-ray film.

Octreotide scan

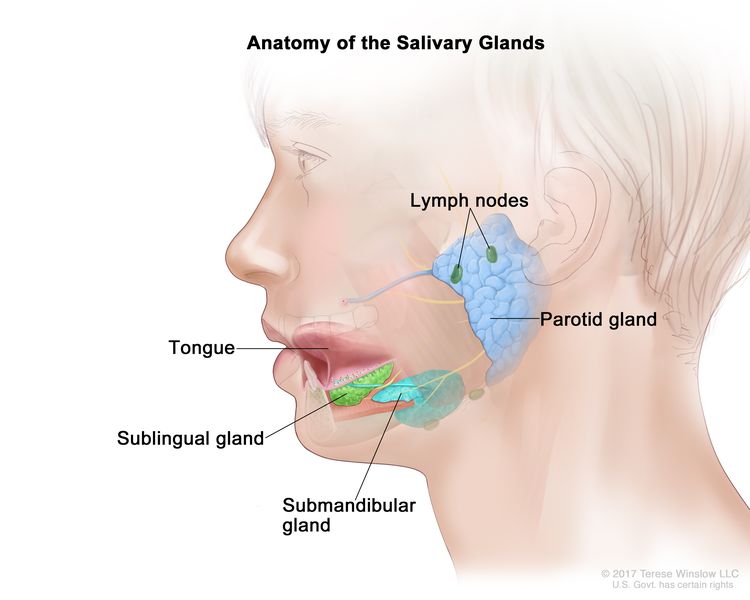

An octreotide scan is a type of radionuclide scan used to find tracheobronchial tumors or cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes. A very small amount of radioactive octreotide (a hormone that attaches to carcinoid tumors) is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive octreotide attaches to the tumor and a special camera that detects radioactivity is used to show where the tumors are in the body.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child’s diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child’s tumor.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, see Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI’s Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor, hospital, or getting a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your child’s appointments, see Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer.

Who treats children with tracheobronchial tumors?

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment of tracheobronchial tumors. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with cancer and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

Treatment of childhood tracheobronchial tumors

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with tracheobronchial tumors. You and your child’s care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child’s overall health and whether the tumor is newly diagnosed or has come back after treatment.

Your child’s treatment plan will include information about the tumor, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child’s care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, see our booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

For all tracheobronchial tumors except rhabdomyosarcoma, treatment might include surgery to remove the tumor. The lymph nodes and vessels where cancer has spread are also removed. Sometimes a surgery called a sleeve resection is done.

For rhabdomyosarcoma in the trachea or bronchi, treatment might include:

- Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment.

- Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. External beam radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer.

Learn more about Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment.

For inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in the trachea or bronchi, in addition to surgery, treatment may include targeted therapy. Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells. Crizotinib may be used if the tumor has a certain change in the ALK gene. Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer.

If the cancer comes back after treatment, your child’s doctor will talk with you about what to expect and possible next steps. There might be treatment options that may shrink the cancer or control its growth. If there are no treatments, your child can receive care to control symptoms from cancer so they can be as comfortable as possible.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your child’s age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Prognosis and prognostic factors for childhood tracheobronchial tumors

If your child has been diagnosed with a tracheobronchial tumor, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and about your child’s chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis depends on many factors, including:

- the type of tracheobronchial tumor

- whether the tumor is or has become cancer and spread to other parts of the body

- whether the tumor was completely removed by surgery

- whether the tumor is newly diagnosed or has come back after treatment

The prognosis for children with tracheobronchial tumors that can be removed by surgery is very good. This is the case for most tracheobronchial tumors except rhabdomyosarcoma, which requires more aggressive treatment.

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child’s cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child’s prognosis.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child’s treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer) or other conditions

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child’s doctors about the possible late effects caused by some treatments.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child’s condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has a tumor, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child’s treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, see Support for Families: Childhood Cancer and the booklet Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Related resources

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, see:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood tracheobronchial tumors. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary (“Updated”) is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become “standard.” Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI’s website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI’s contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Tracheobronchial Tumors. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: /types/lung/patient/child-tracheobronchial-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>.

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.