Treatment of Bladder Cancer by Stage

Bladder cancer stage and grade are important factors in deciding the best treatment for bladder cancer. Other factors, such as your preferences and overall health, are also important.

Palliative therapy aims to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life for people with life-threatening diseases like cancer. It is helpful at all stages of cancer. Many cancer treatments can also be used as palliative therapy to enhance comfort. Learn more about Palliative Care in Cancer.

For some people, taking part in a clinical trial of new cancer drugs or treatment combinations may be an option. To learn about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, visit Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment of stages 0 and I bladder cancer

Stage 0 and stage I bladder cancer, also known as non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), haven’t spread to the muscle layer of the bladder. Treatment of NMIBC depends on several factors:

- the risk level of the cancer (low, intermediate, or high) for recurrence or becoming muscle-invasive

- the stage and grade of the cancer

- the size and number of tumors

The first treatment is usually a surgical procedure called transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration to remove the tumor. Sometimes, surgery might be repeated if the first doesn’t remove enough of the tumor or does not include a sample from the muscle layer. If a repeat surgery finds that the cancer has invaded the muscle layer, it will be treated as muscle-invasive bladder cancer (stage II bladder cancer or higher).

Because stage 0 and stage I bladder cancer often come back after surgery, most people receive intravesical chemotherapy with mitomycin or gemcitabine or intravesical BCG at the time of their first surgery. To help lower the risk of bladder cancer recurrence, your doctor may recommend you continue having intravesical BCG for up to 3 years, depending on the characteristics of the cancer. This is called maintenance therapy.

To learn more about the treatments below, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of low-risk bladder cancer

Low-risk bladder cancer might include small, single, low-grade tumors.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration and intravesical therapy given around the time of surgery, followed by surveillance. Surveillance means closely watching your condition but not giving any treatment unless the cancer returns.

Treatment of intermediate-risk bladder cancer

Intermediate-risk bladder cancer might include multiple or large, slow-growing stage 0a tumors, slow-growing stage 0a tumors that recur within 1 year, a single fast-growing stage 0a tumor, or a slow-growing stage I tumor.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration, followed by intravesical therapy (BCG or chemotherapy with mitomycin or gemcitabine). Depending on the characteristics of the cancer, your doctor may recommend that you continue having intravesical BCG for up to 1 year to lower the risk of recurrence. Surveillance with regular cystoscopies (bladder inspections with a camera) and possibly additional imaging tests are used to monitor for signs of cancer recurrence or progression.

Treatment of high-risk bladder cancer

High-risk bladder cancer might include multiple or large high-grade stage 0a tumors, the presence of carcinoma in situ (stage 0is), and fast-growing stage I tumors.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration, followed by intravesical BCG therapy. Sometimes, intravesical BCG is continued for up to 3 years to lower the risk of recurrence. If you have multiple tumors or carcinoma in situ, a type of high-grade stage 0 cancer, another option is surgery to remove part or all of your bladder (cystoscopy).

Treatment of very high-risk bladder cancer

Very high-risk bladder cancer might include cancer that does not respond to intravesical BCG, that recurs in the urethra, or that involves cancer cells detected in the blood or lymph system near the tumor. Very high-risk bladder cancer has a greater chance of progressing to muscle-invasive disease (stage II or higher).

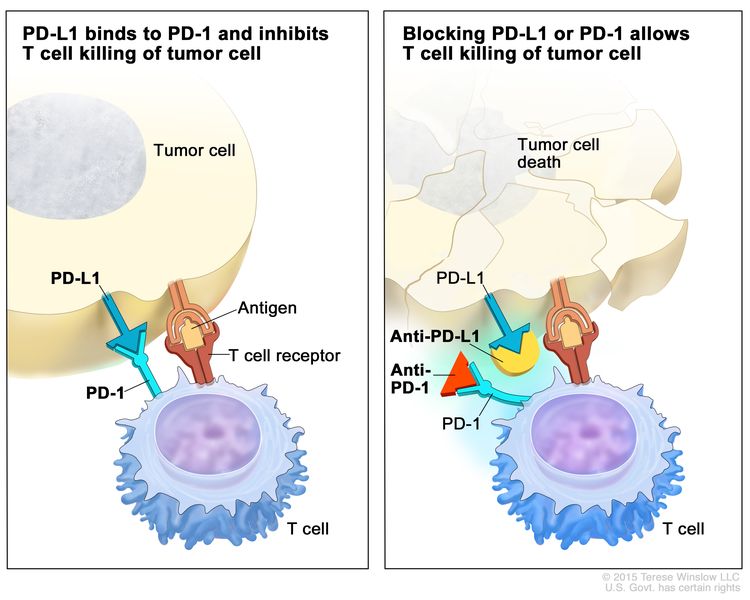

If you have many tumors or carcinoma in situ (a type of high-grade stage 0 cancer), partial or complete cystectomy (surgical removal of the bladder) may be an option. If you have carcinoma in situ, cannot or choose not to have a cystectomy, and BCG did not work, other options include intravesical chemotherapy, the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab given through a vein, or intravesical immunotherapy with nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg or nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln.

Treatment of stages II and III bladder cancer

The two main treatments for stage II and stage III bladder cancer are radical cystectomy or a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Radical cystectomy is surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding tissues and organs. Surgery to make a new way for urine to leave the body (called urinary diversion) will be done. Additional treatments may be given before or after surgery:

- Chemotherapy may be given before surgery to people who are well enough to tolerate it. Giving combination chemotherapy that includes cisplatin before surgery has been shown to help people live longer than surgery alone.

- The immunotherapy drug nivolumab may be given if the cancer has a high risk of coming back after surgery or did not respond to chemotherapy.

If you are unable or choose not to have surgery, treatment may include a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy, such as cisplatin and fluorouracil, given at the same time. Giving chemotherapy at the same time as radiation therapy helps the radiation therapy work better.

Partial cystectomy (removal of part of the bladder) is a less common treatment for stages II and III bladder cancer.

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of stage IV bladder cancer

Treatment for stage IV bladder cancer depends on whether the cancer is locally advanced or metastatic. Treatment for metastatic bladder cancer is aimed at relieving symptoms and improving quality of life while also slowing the growth and spread of the cancer.

Treatment of stage IVA (locally advanced) bladder cancer may include:

- the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab in combination with the targeted therapy drug enfortumab vedotin

- the immunotherapy drug nivolumab in combination with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine

- the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by the immunotherapy drug avelumab

- for people well enough to tolerate it, cisplatin-based systemic chemotherapy, such as one of the following regimens:

- pembrolizumab alone

- a cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimen followed by surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding tissues and organs (radical cystectomy) and urinary diversion or surgery alone

- radiation therapy and chemotherapy, such as cisplatin and fluorouracil, given at the same time, to help the radiation therapy work better

- urinary diversion, as palliative therapy or to prevent a blockage of urine that could cause kidney damage

- surgery to remove part or all of the bladder (cystectomy) as palliative therapy

Treatment of stage IVB (metastatic) bladder cancer may include:

- the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab in combination with the targeted therapy drug enfortumab vedotin

- the immunotherapy drug nivolumab in combination with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine

- the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by the immunotherapy drug avelumab

- systemic chemotherapy, such as one of the following regimens:

- gemcitabine with either cisplatin or carboplatin

- dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC)

- cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine (CMV)

- an immunotherapy drug alone, such as avelumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab

- radiation therapy as palliative therapy

- urinary diversion, as palliative therapy or to prevent a blockage of urine that could damage the kidneys

- surgery to remove part or all of the bladder (cystectomy) as palliative therapy

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of recurrent bladder cancer

Treatment of bladder cancer that has recurred (come back) depends on previous treatment and where the cancer has come back. Treatment may include:

- systemic chemotherapy, such one of the following regimens:

- gemcitabine with either cisplatin or carboplatin

- dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC)

- cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine

- an immunotherapy drug, such as avelumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab

- a targeted therapy drug, such as enfortumab vedotin, erdafitinib, or ramucirumab

- surgery for non-muscle-invasive or localized tumors, which may be followed by immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- radiation therapy as palliative therapy

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.