Disease Overview for Primary Myelofibrosis (PMF)

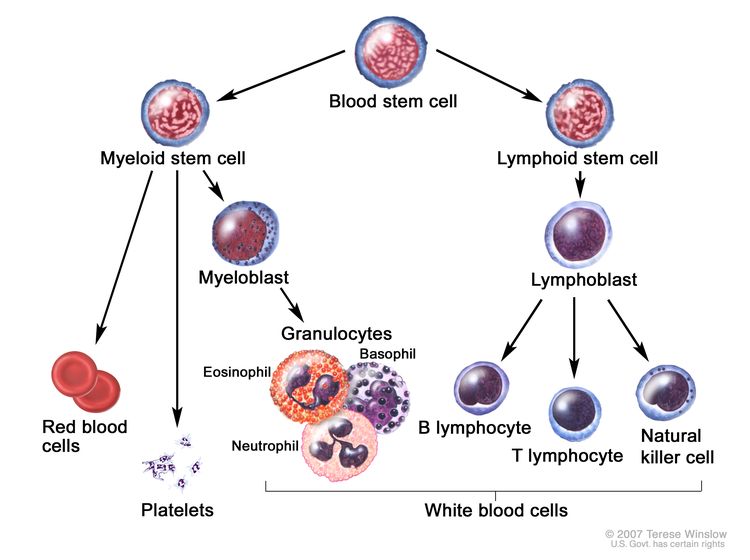

PMF (also known as agnogenic myeloid metaplasia, chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis, myelosclerosis with myeloid metaplasia, and idiopathic myelofibrosis) is characterized by splenomegaly, immature peripheral blood granulocytes and erythrocytes, and teardrop-shaped red blood cells.[1] In its early phase, the disease is characterized by elevated numbers of CD34-positive cells in the marrow, while the later phases involve marrow fibrosis with decreasing CD34 cells in the marrow and a corresponding increase in splenic and liver engorgement with CD34 cells.

As distinguished from chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), PMF usually presents as follows:[2]

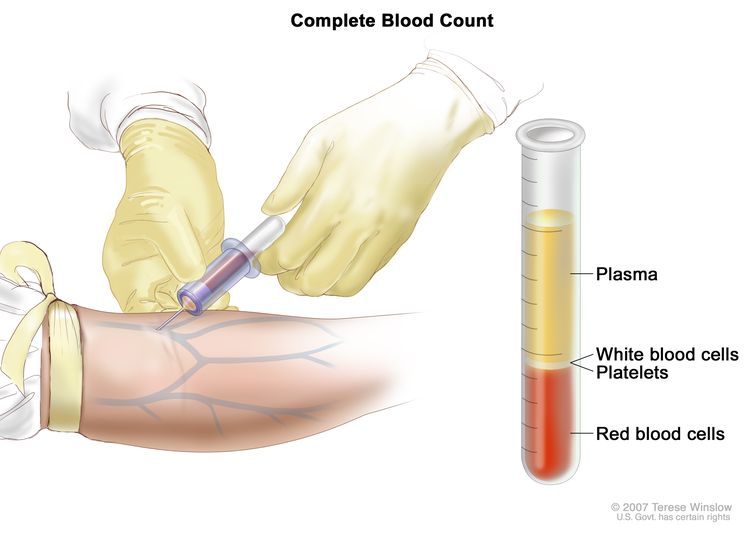

- A white blood cell count less than 30 × 109/L.

- Prominent teardrops on peripheral smear.

- Normocellular or hypocellular marrow with moderate to marked fibrosis.

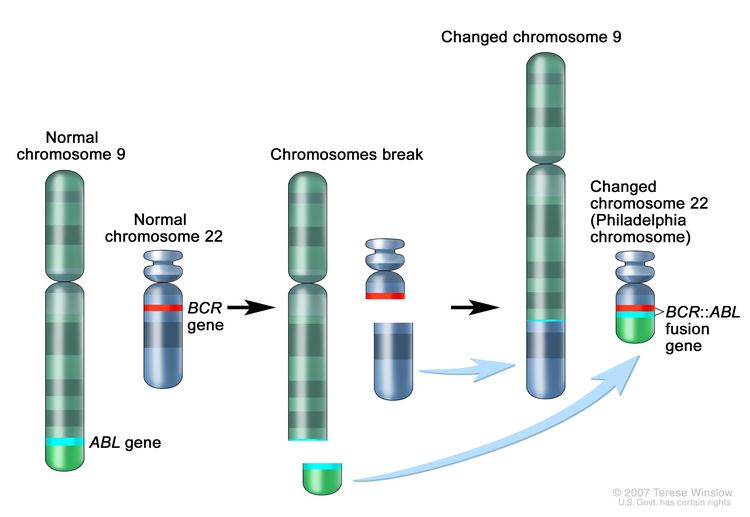

- An absence of the Philadelphia chromosome or the BCR::ABL translocation.

- Identification of a JAK2, MPL, or CALR variant (70% of patients).[3–5]

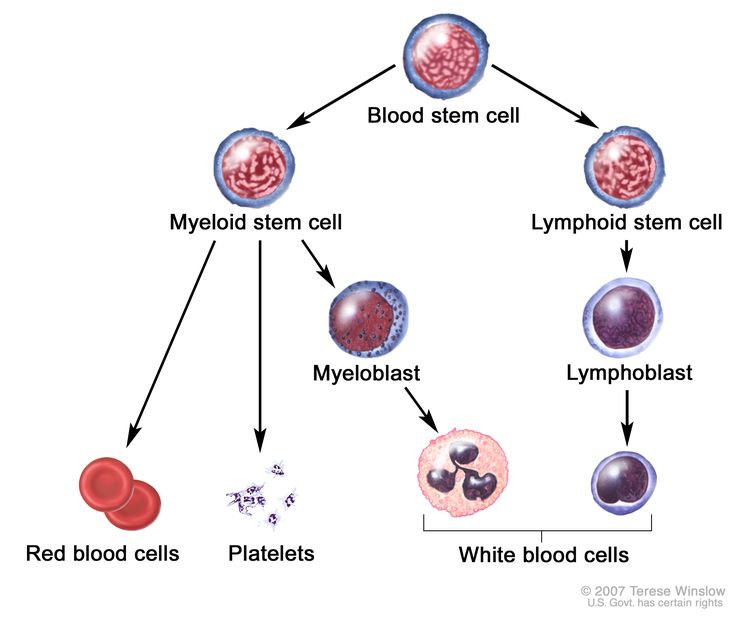

In addition to the clonal proliferation of a multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cell, an event common to all chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms, myeloid metaplasia is characterized by colonization of extramedullary sites such as the spleen or liver.[6,7]

Most patients are older than 60 years at diagnosis, and 33% of patients are asymptomatic at presentation. Splenomegaly, sometimes massive, is a characteristic finding. Patients younger than 40 years have a more indolent course, with fewer thrombotic events or transformation to acute leukemia.[8]

Symptoms of PMF include:

- Splenic pain.

- Early satiety.

- Anemia.

- Bone pain.

- Fatigue.

- Fever.

- Night sweats.

- Weight loss.

For more information about the symptoms listed above, see Fatigue, Hot Flashes and Night Sweats, and Nutrition in Cancer Care.

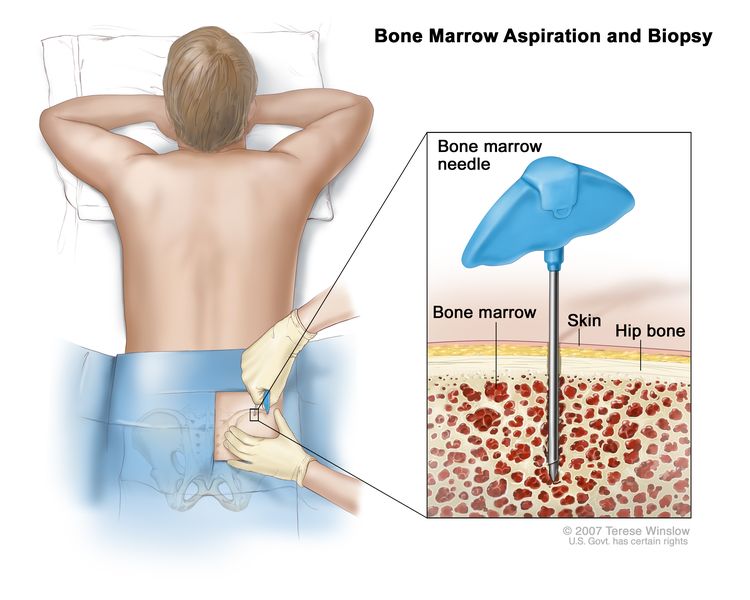

To establish a diagnosis of PMF, the World Health Organization classification requires that the patient meet all three major criteria and two minor criteria.[9]

Major Criteria

- Megakaryocyte proliferation and atypia, usually accompanied by either reticulin and/or collagen fibrosis; or, in the absence of significant reticulin fibrosis, the megakaryocyte changes must be accompanied by increased bone marrow cellularity characterized by granulocytic proliferation and often decreased erythropoiesis (so-called prefibrotic cellular-phase disease).

- Not meeting criteria for polycythemia vera (PV), CML, myelodysplastic syndrome, or other myeloid neoplasm.

- Demonstration of JAK2 V617F or other clonal marker; or, in the absence of a clonal marker, no evidence of bone marrow fibrosis caused by an underlying inflammatory disease or another neoplastic disease. About 60% of patients with PMF carry a JAK2 variant, and about 5% to 10% of the patients have activating variants in the thrombopoietin receptor gene, MPL. More than half of the patients without JAK2 or MPL carry a somatic pathogenic variant in the CALR gene, which is associated with a more indolent clinical course than that seen in patients with JAK2 or MPL variants.[3–5,10–12]

Minor Criteria

- Leukoerythroblastosis.

- Increased serum lactate dehydrogenase level.

- Anemia.

- Palpable splenomegaly.

The major causes of death include:[13]

- Progressive marrow failure.

- Transformation to acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia.[14]

- Infection.

- Thrombohemorrhagic events.[15]

- Heart failure.

- Portal hypertension.

Fatal and nonfatal thrombosis was associated with age older than 60 years and JAK2 V617F positivity in a multivariable analysis of 707 patients followed from 1973 to 2008.[16] Bone marrow examination including cytogenetic testing may exclude other causes of myelophthisis, such as CML, myelodysplastic syndrome, metastatic cancer, lymphomas, and plasma cell disorders.[7] In acute myelofibrosis, patients present with pancytopenia but no splenomegaly or peripheral blood myelophthisis. Peripheral blood or marrow monocytosis is suggestive for myelodysplasia in this setting.

There is no staging system for this disease.

Prognostic factors include:[17–21]

- Age 65 years or older.

- Anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL).

- Constitutional symptoms: fever, night sweats, or weight loss.

- Leukocytosis (white blood cell count >25 × 109/L).

- Circulating blasts of at least 1%.

Patients without any of the adverse features, excluding age, have a median survival of more than 10 to 15 years, but the presence of any two of the adverse features lowers the median survival to less than 4 years.[22,23] International prognostic scoring systems incorporate the aforementioned prognostic factors.[22,24] Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50 × 109/L) is a very poor prognostic factor for PMF and for myelofibrosis following thrombocythemia or PV.[25]

Karyotype abnormalities can also affect prognosis. In a retrospective series, the 13q and 20q deletions and trisomy 9 correlated with improved survival and no leukemia transformation in comparison with the worse prognosis with trisomy 8, complex karyotype, -7/7q-, i(17q), inv(3), -5/5q-, 12p-, or 11q23 rearrangement.[16,26]

Treatment Options for PMF

Treatment options for PMF include:

- Ruxolitinib.[37–40]

- Clinical trials involving other JAK2 inhibitors.

- Hydroxyurea.[6,7]

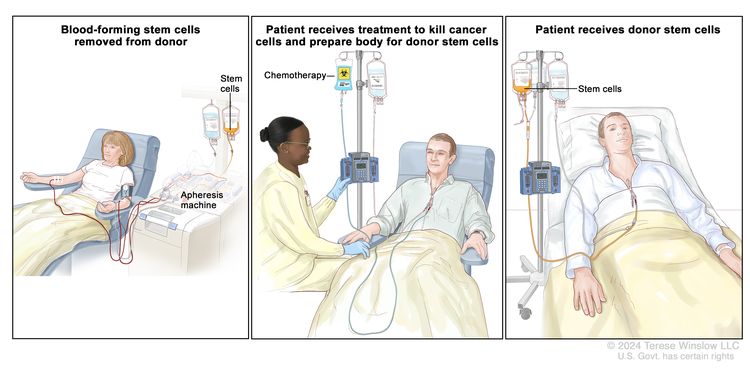

- Allogeneic peripheral stem cell or bone marrow transplant.[41–45]

- Thalidomide.[27,32,46–49]

- Lenalidomide.[29,33–35,49]

- Pomalidomide.[36]

- Splenectomy.[50,51]

- Splenic radiation therapy or radiation to sites of symptomatic extramedullary hematopoiesis (e.g., large lymph nodes, cord compression).[7]

- Cladribine.[52]

- Interferon alfa.[53,54]

Cytoreductive therapy

Ruxolitinib, an inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, can reduce the splenomegaly and debilitating symptoms of weight loss, fatigue, and night sweats for patients with JAK2-positive or JAK2-negative PMF, post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis, or post-PV myelofibrosis.[55]

Evidence (cytoreductive therapy):

- In two prospective randomized trials, 528 higher-risk patients were randomly assigned to ruxolitinib or to either placebo (COMFORT-I [NCT00952289]) or best-available therapy (COMFORT-II [NCT00934544]).[37,38]

- At 48 weeks, patients who received ruxolitinib had a decrease of 30% to 40% in mean spleen volume compared with an increase of 7% to 8% in the control patients.[37,38][Level of evidence B3]

- Ruxolitinib also improved overall quality-of-life measures, with low toxic effects in both studies, but with no benefit in overall survival in the initial reports.

- Additional follow-up in both studies (5 years in COMFORT-I and in COMFORT-II) showed a survival benefit (statistically significant only for COMFORT-I) among patients who received ruxolitinib compared with control patients (COMFORT-I hazard ratio [HR], 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.96; P = .025; and COMFORT-II HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.44–1.02; P = .06).[56,57][Level of evidence A1]

- Clinical benefits were observed across a wide variety of clinical subgroups.[58,59]

Discontinuation of ruxolitinib results in a rapid worsening of splenomegaly and the recurrence of systemic symptoms.[37–39] Ruxolitinib does not reverse bone marrow fibrosis or induce histological or cytogenetic remissions. Aggressive B-cell lymphomas have occurred among patients treated with ruxolitinib when a preexisting clonal B-cell population was identified at diagnosis in conjunction with myelofibrosis.[60]

Treatment of splenomegaly

Painful splenomegaly can be treated temporarily with ruxolitinib, hydroxyurea, thalidomide, lenalidomide, cladribine, or radiation therapy, but sometimes requires splenectomy.[29,50,61] The decision to perform splenectomy represents a weighing of the benefits (i.e., reduction of symptoms, decreased portal hypertension, and less need for red blood cell transfusions lasting for 1 to 2 years) versus the debits (i.e., postoperative mortality of 10% and morbidity of 30% caused by infection, bleeding, or thrombosis; no benefit for thrombocytopenia; and accelerated progression to the blast-crisis phase that was seen by some investigators but not others).[7,50]

After splenectomy, many physicians use anticoagulation therapy for 4 to 6 weeks to reduce portal vein thrombosis. Hydroxyurea can be used to reduce high platelet levels (>1 million).[62] However, in a retrospective review of 150 patients who underwent surgery, 8% of the patients had a thromboembolism and 7% had a major hemorrhage with prior cytoreduction and postoperative subcutaneous heparin used in one-half of the patients.[63]

Hydroxyurea is useful in patients with splenomegaly but may have a leukemogenic effect.[7] In patients with thrombocytosis and hepatomegaly after splenectomy, cladribine may be an alternative to hydroxyurea.[52] The use of interferon alfa may result in hematological responses, including reduction in spleen size in 30% to 50% of patients, though many patients do not tolerate this medication.[53,54] Favorable responses to thalidomide and lenalidomide have been reported in about 20% to 60% of patients.[27–29,47–49][Level of evidence C3]

A more aggressive approach involves allogeneic peripheral stem cell or bone marrow transplant when a suitable donor is available.[41–46] Allogeneic stem cell transplant is the only potentially curative treatment available, but the associated morbidity and mortality limit its use to younger, high-risk patients.[44,64] Detection of a JAK2 variant after transplant is associated with a worse prognosis.[65]