List of Targeted Therapy Drugs Approved for Specific Types of Cancer

The FDA has approved targeted therapy drugs for the treatment of some people with the following types of cancer. Some targeted therapy drugs are listed more than once because they have been approved to treat more than one type of cancer. The generic drug name is listed first, with a brand name in parentheses.

Targeted therapy approved for bladder cancer

Targeted therapy approved for brain cancer

Targeted therapy approved for breast cancer

- abemaciclib (Verzenio)

- ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla)

- alpelisib (Piqray)

- anastrozole (Arimidex)

- capivasertib (Truqap)

- datopotamab deruxtecan-dlnk (Datroway)

- elacestrant dihydrochloride (Orserdu)

- everolimus (Afinitor)

- exemestane (Aromasin)

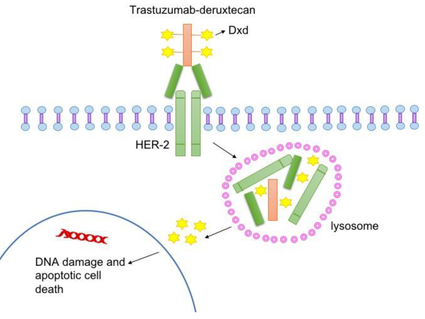

- fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki (Enhertu)

- fulvestrant (Faslodex)

- goserelin acetate (Zoladex)

- inavolisib (Itovebi)

- lapatinib ditosylate (Tykerb)

- letrozole (Femara)

- margetuximab-cmkb (Margenza)

- neratinib maleate (Nerlynx)

- olaparib (Lynparza)

- palbociclib (Ibrance)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- pertuzumab (Perjeta)

- pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and hyaluronidase-zzxf (Phesgo)

- ribociclib (Kisqali)

- ribociclib succinate and letrozole (Kisquali Femara Co-Pack)

- sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (Trodelvy)

- talazoparib tosylate (Talzenna)

- tamoxifen citrate (Soltamox)

- toremifene (Fareston)

- trastuzumab (Herceptin)

- tucatinib (Tukysa)

Targeted therapy approved for cervical cancer

Targeted therapy approved for colorectal cancer

- adagrasib (Krazati)

- bevacizumab (Avastin)

- cetuximab (Erbitux)

- encorafenib (Braftovi)

- fruquintinib (Fruzalqa)

- ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- panitumumab (Vectibix)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- ramucirumab (Cyramza)

- regorafenib (Stivarga)

- sotorasib (Lumakras)

- tucatinib (Tukysa)

- ziv-aflibercept (Zaltrap)

Targeted therapy approved for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Targeted therapy approved for endocrine and neuroendocrine tumors

Targeted therapy approved for endometrial cancer

Targeted therapy approved for esophageal cancer

Targeted therapy approved for head and neck cancer

Targeted therapy approved for gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Targeted therapy approved for giant cell tumor

Targeted therapy approved for kidney cancer

- avelumab (Bavencio)

- axitinib (Inlyta)

- belzutifan (Welireg)

- bevacizumab (Avastin)

- cabozantinib-s-malate (Cabometyx)

- everolimus (Afinitor)

- ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- lenvatinib mesylate (Lenvima)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- pazopanib hydrochloride (Votrient)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- sorafenib tosylate (Nexavar)

- sunitinib malate (Sutent)

- temsirolimus (Torisel)

- tivozanib hydrochloride (Fotivda)

Targeted therapy approved for leukemia

- acalabrutinib (Calquence)

- alemtuzumab (Campath)

- asciminib hydrochloride (Scemblix)

- avapritinib (Ayvakit)

- blinatumomab (Blincyto)

- bosutinib (Bosulif)

- brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus)

- dasatinib (Sprycel)

- duvelisib (Copiktra)

- enasidenib mesylate (Idhifa)

- gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg)

- gilteritinib fumarate (Xospata)

- glasdegib maleate (Daurismo)

- ibrutinib (Imbruvica)

- idelalisib (Zydelig)

- imatinib mesylate (Gleevec)

- inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa)

- ivosidenib (Tibsovo)

- lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi)

- midostaurin (Rydapt)

- nilotinib (Tasigna)

- obecabtagene autoleucel (Aucatzyl)

- obinutuzumab (Gazyva)

- ofatumumab (Arzerra)

- olutasidenib (Rezlidhia)

- pemigatinib (Pemazyre)

- pirtobrutinib (Jaypirca)

- ponatinib hydrochloride (Iclusig)

- quizartinib dihydrochloride (Vanflyta)

- revumenib citrate (Revuforj)

- rituximab (Rituxan)

- rituximab and hyaluronidase human (Rituxan Hycela)

- tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris)

- tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah)

- tretinoin (Vesanoid)

- venetoclax (Venclexta)

- zanubrutinib (Brukinsa)

Targeted therapy approved for liver and bile duct cancer

- atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

- atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq Hybreza)

- bevacizumab (Avastin)

- cabozantinib-s-malate (Cabometyx)

- durvalumab (Imfinzi)

- futibatinib (Lytgobi)

- ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- ivosidenib (Tibsovo)

- lenvatinib mesylate (Lenvima)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- pemigatinib (Pemazyre)

- ramucirumab (Cyramza)

- regorafenib (Stivarga)

- sorafenib tosylate (Nexavar)

- tremelimumab-actl (Imjudo)

- zanidatamab-hrii (Ziihera)

Targeted therapy approved for lung cancer

- adagrasib (Krazati)

- afatinib dimaleate (Gilotrif)

- alectinib (Alecensa)

- amivantamab-vmjw (Rybrevant)

- atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

- atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq Hybreza)

- bevacizumab (Avastin)

- binimetinib (Mektovi)

- brigatinib (Alunbrig)

- capmatinib hydrochloride (Tabrecta)

- cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo)

- ceritinib (Zykadia)

- crizotinib (Xalkori)

- dabrafenib mesylate (Tafinlar)

- dacomitinib (Vizimpro)

- durvalumab (Imfinzi)

- encorafenib (Braftovi)

- ensartinib hydrochloride (Ensacove)

- entrectinib (Rozlytrek)

- erlotinib hydrochloride (Tarceva)

- fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki (Enhertu)

- gefitinib (Iressa)

- ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- lazertinib mesylate hydrate (Lazcluze)

- lorlatinib (Lorbrena)

- necitumumab (Portrazza)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- osimertinib mesylate (Tagrisso)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- pralsetinib (Gavreto)

- ramucirumab (Cyramza)

- repotrectinib (Augtyro)

- selpercatinib (Retevmo)

- sotorasib (Lumakras)

- tarlatamab-dlle (Imdelltra)

- tepotinib hydrochloride (Tepmetko)

- trametinib dimethyl sulfoxide (Mekinist)

- tremelimumab-actl (Imjudo)

- zenocutuzumab-zbco (Bizengri)

Targeted therapy approved for lymphoma

- acalabrutinib maleate monohydrate (Calquence)

- axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta)

- belinostat (Beleodaq)

- bexarotene (Targretin)

- bortezomib (Velcade)

- brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris)

- brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus)

- crizotinib (Xalkori)

- denileukin diftitox-cxdl (Lymphir)

- duvelisib (Copiktra)

- epcoritamab-bysp (Epkinly)

- glofitamab-gxbm (Columvi)

- ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin)

- ibrutinib (Imbruvica)

- lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi)

- loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl (Zynlonta)

- mogamulizumab-kpkc (Poteligeo)

- mosunetuzumab-axgb (Lunsumio)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- obinutuzumab (Gazyva)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- pemigatinib (Pemazyre)

- pirtobrutinib (Jaypirca)

- polatuzumab vedotin-piiq (Polivy)

- pralatrexate (Folotyn)

- rituximab (Rituxan)

- rituximab and hyaluronidase human (Rituxan Hycela)

- romidepsin (Istodax)

- selinexor (Xpovio)

- siltuximab (Sylvant)

- tafasitamab-cxix (Monjuvi)

- tazemetostat hydrobromide (Tazverik)

- tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah)

- venetoclax (Venclexta)

- vorinostat (Zolinza)

- zanubrutinib (Brukinsa)

Targeted therapy approved for malignant mesothelioma

Targeted therapy approved for multiple myeloma

- bortezomib (Velcade)

- carfilzomib (Kyprolis)

- ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Carvykti)

- daratumumab (Darzalex)

- daratumumab and hyaluronidase-fihj (Darzalex Faspro)

- elranatamab-bcmm (Elrexfio)

- elotuzumab (Empliciti)

- idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma)

- isatuximab-irfc (Sarclisa)

- ixazomib citrate (Ninlaro)

- talquetamab-tgvs (Talvey)

- selinexor (Xpovio)

- teclistamab-cqyv (Tecvayli)

Targeted therapy approved for myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative disorders

Targeted therapy approved for neuroblastoma

Targeted therapy approved for ovarian epithelial, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers

Targeted therapy approved for pancreatic cancer

Targeted therapy approved for plexiform neurofibroma

Targeted therapy approved for prostate cancer

- abiraterone acetate (Zytiga)

- apalutamide (Erleada)

- bicalutamide (Casodex)

- cabazitaxel (Jevtana)

- darolutamide (Nubeqa)

- degarelix (Firmagon)

- enzalutamide (Xtandi)

- flutamide

- goserelin acetate (Zoladex)

- leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot, Eligard)

- leuprolide mesylate (Camcevi)

- lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto)

- nilutamide (Nilandron)

- niraparib tosylate monohydrate and abiraterone acetate (Akeega)

- olaparib (Lynparza)

- talazoparib tosylate (Talzenna)

- radium 223 dichloride (Xofigo)

- relugolix (Orgovyx)

- rucaparib camsylate (Rubraca)

- triptorelin pamoate (Trelstar)

Targeted therapy approved for skin cancer

- alitretinoin (Panretin)

- atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

- atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq Hybreza)

- avelumab (Bavencio)

- binimetinib (Mektovi)

- cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo)

- cobimetinib fumarate (Cotellic)

- cosibelimab-ipdl (Unloxcyt)

- dabrafenib mesylate (Tafinlar)

- encorafenib (Braftovi)

- ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- nivolumab (Opdivo)

- nivolumab and relatlimab-rmbw (Opdualag)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- retifanlimab-dlwr (Zynyz)

- sonidegib (Odomzo)

- tebentafusp-tebn (Kimmtrak)

- trametinib dimethyl sulfoxide (Mekinist)

- vismodegib (Erivedge)

- vemurafenib (Zelboraf)

Targeted therapy approved for soft tissue sarcoma

- afamitresgene autoleucel (Tecelra)

- alitretinoin (Panretin)

- atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

- atezolizumab and hyaluronidase-tqjs (Tecentriq Hybreza)

- crizotinib (Xalkori)

- nirogacestat hydrobromide (Ogsiveo)

- pazopanib hydrochloride (Votrient)

- sirolimus protein-bound particles (Fyarro)

- tazemetostat hydrobromide (Tazverik)

Targeted therapy approved for solid tumors anywhere in the body

Targeted therapy approved for stomach (gastric) cancer

Targeted therapy approved for systemic mastocytosis

Targeted therapy approved for thyroid cancer